The Object–Portal Method

Metodología del objeto - portal

L.A./001

∴

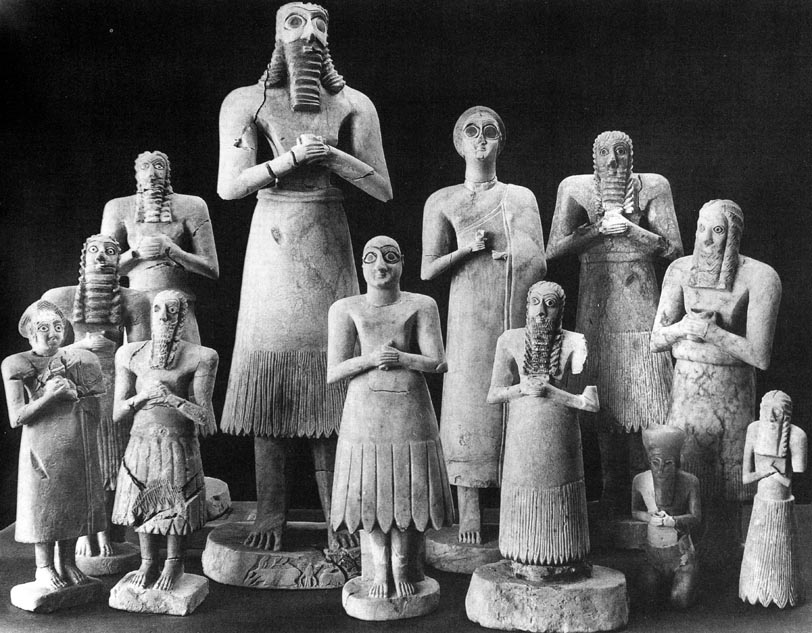

Since the earliest cultures, objects have been understood as more than mere tools. In the Paleolithic era, the Venus figurines carved from stone or ivory embodied symbols linked to fertility and the continuity of life. In Mesopotamia, votive figures were left in temples to maintain a constant presence before the divine, even when the person was no longer there. In Egypt, funerary amulets protected the deceased during their journey to the afterlife, and in Mesoamerica, jade masks were placed over the faces of the dead as keys granting access to another existence. In all these cases, the object was not a simple material artifact: it functioned as a threshold between the visible world and another dimension.

During the Middle Ages, this vision continued in new forms. Gothic reliquaries, crafted in gold and crystal, were not merely containers for sacred fragments—they became centers of devotion and points of contact between the earthly and the divine. In the twentieth century, artists such as Louise Nevelson built black wooden altars from assembled fragments, transforming urban remnants into contemplative architectures. Today, Belgian painter and sculptor Renato Nicolodi designs concrete structures that resemble sealed bunkers—architectural forms with steps and tiers ascending toward inner chambers and cloisters. His works evoke the solemnity of an absent temple, exploring the human experience of eternity and transcendence through time and space.

Cinema has also explored this condition of objects and spaces as passages. In Stalker (1979), Andrei Tarkovsky conceived the Zone as a physical place of ruins and rusted metal, but also as a space that transforms those who cross it. It was not an abstract symbol—it was a tangible, material environment that altered perception.

It is within this genealogy—from prehistoric amulets to Tarkovsky—that the methodology of the “object-portal” takes shape: a working approach at Las Ánimas in which each piece, and each space that receives it, is conceived as a place of transit—a form that links the material with the symbolic, not by inventing meanings, but by relying on the reality of matter and on tangible cultural references.

Desde las primeras culturas, los objetos fueron entendidos como algo más que herramientas. En el Paleolítico, las venus esculpidas en piedra o marfil condensaban símbolos ligados a la fertilidad y la permanencia de la vida. En Mesopotamia, las figuras votivas se dejaban en los templos para mantener una presencia constante ante lo divino, incluso cuando la persona ya no estaba allí. En Egipto, los amuletos funerarios protegían al difunto durante el viaje al más allá, y en Mesoamérica, las máscaras de jade se colocaban sobre el rostro de los muertos como llaves para acceder a otra existencia. En todos estos casos, el objeto no era un simple artefacto material: cumplía la función de umbral entre el mundo visible y otra dimensión.

En la Edad Media, esta visión continuó con nuevas formas. Los relicarios góticos, trabajados en oro y cristal, no eran solo contenedores de fragmentos sagrados: se convertían en centros de devoción y en puntos de contacto entre lo terrenal y lo divino. En el siglo XX, artistas como Louise Nevelson construyeron altares de madera negra ensamblada, capaces de transformar restos urbanos en arquitecturas contemplativas. Y en la actualidad, el pintor y escultor belga Renato Nicolodi diseña estructuras en hormigón que parecen bunkers sellados, estructuras arquitectónicas con gradas y escaleras que ascienden hacia interiores, cámaras y claustros: formas que evocan la solemnidad de un templo ausente, explorando la experiencia humana de la eternidad y la trascendencia a través del tiempo y del espacio.

El cine también ha explorado esta condición de los objetos y los espacios como pasajes. En Stalker (1979), Andrei Tarkovski concibió la Zona como un lugar físico de ruinas y hierros oxidados, pero también como un espacio que altera a quienes lo atraviesan. No era un símbolo abstracto: era un entorno material y concreto que modificaba la percepción.

Es en esta genealogía, desde los amuletos prehistóricos hasta Tarkovski, donde se sitúa la metodología del objeto-portal: un modo de trabajar en Las Ánimas en el que cada pieza y cada espacio que la acoge se piensan como un lugar de tránsito, una forma que enlaza lo material con lo simbólico sin necesidad de inventar significados, sino apoyándose en la realidad de la materia y en referencias culturales tangibles.

The process always begins with something minimal: a line in a notebook, a found word, an architectural fragment collected during a journey. That initial spark is the seed of the object. What follows is a patient unfolding. First, on a conceptual level—delving into the idea, letting it rest, returning to it. Then, at the drawing table, on paper, in front of the computer. And finally, in the workshop, where the idea, the concept, and the sketch are transformed into matter, and matter evolves through successive layers of work.

Wood, worked until its veins become lines of energy; slaked lime, applied in mixtures that require rest, as in ancestral building techniques; concrete, gaining volume in molds and fracturing into edges; or resin, trapping bubbles and veils that can never be repeated. Each of these gestures leaves traces—marks of time that turn the piece into a stratified archive.

At this stage, the workshop moves away from any notion of an assembly line. What happens there is closer to a ritual of repetition. Cutting, sanding, assembling, pigmenting: each action is repeated until it acquires symbolic weight. Accident, far from being an error, becomes a revelation. An unexpected grain in the wood, a trapped bubble in the resin, or a crack in the mortar are not concealed—they are integrated as part of the object’s life. Like an analogue glitch opening a breach toward the unexpected, these accidents are gateways to the unknown within the material.

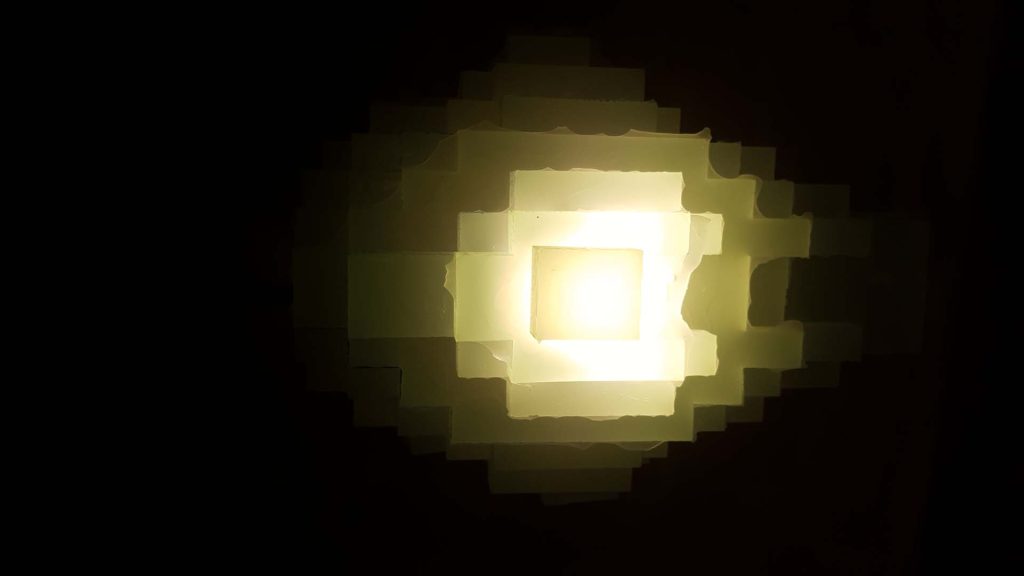

The finished object is never a closed product. A lamp can radically transform a space by projecting liquid reflections onto walls and ceilings, generating a climate of strangeness. A relief can be read as an archaeological map of an imaginary territory. A table can acquire the solemnity of an altar, where practical use intertwines with symbolic presence. In all these pieces, what emerges is a space for focus and contemplation—where the viewer pauses, perceives, and enters into another relationship with reality.

El recorrido comienza siempre con algo mínimo: un trazo en un cuaderno, una palabra encontrada, un fragmento arquitectónico recogido en un viaje. Esa chispa inicial es la semilla del objeto. Lo que sigue es un trabajo paciente. Primero a nivel conceptual, ahondar en la idea, dejarla reposar, volver a ella. Luego en la mesa de dibujo, ante el papel, delante del ordenador. Y en el taller, donde la idea, el concepto y el boceto se transforman en materia, y la materia evoluciona mediante capas de trabajo sucesivas. La madera, trabajada hasta que las vetas se convierten en líneas de energía; la cal muerta, aplicada en mezclas que necesitan reposo, como en las técnicas ancestrales de construcción; el hormigón, que adquiere volumen en moldes y se fractura en aristas; o la resina que atrapa burbujas y veladuras imposibles de repetir. Cada uno de esos gestos deja huellas: rastros de tiempo que convierten la pieza en un archivo estratificado.

En este punto, el taller se aleja de cualquier idea de cadena de montaje. Lo que ocurre allí se aproxima más a un ritual de repetición. Cortar, lijar, ensamblar, pigmentar: cada acción se repite hasta adquirir un peso simbólico. El accidente, lejos de ser un error, es una revelación. Una veta inesperada en la madera, una burbuja atrapada en la resina o una grieta en el mortero no se ocultan: se integran como parte de la vida del objeto. Como un glitch analógico, que abre un hueco hacia lo inesperado, estos accidentes son puertas de entrada a lo desconocido dentro de lo material.

El objeto terminado nunca es un producto cerrado. Una lámpara puede modificar radicalmente un espacio al proyectar reflejos líquidos sobre paredes y techos, generando un clima de extrañeza. Un relieve puede leerse como un mapa arqueológico de un territorio imaginario. Una mesa puede adquirir la solemnidad de un altar, donde el uso práctico se mezcla con una presencia simbólica. En todas estas piezas, lo que aparece es un espacio de concentración y contemplación, donde el espectador se detiene, percibe y entra en otra relación con lo real.

The Object–Portal Methodology is grounded in two main axes: the real work of the workshop and the cultural memories that permeate each piece. On one side, the tangible materials and the visible traces left by repeated gestures. On the other, a genealogy that connects amulets, reliquaries, architectures, and cinematic landscapes.

Through this lens, objects can become thresholds. Each piece by Las Ánimas is a tangible, present object, yet at the same time a place where the everyday opens onto another dimension. Like ancient altars, these works invite passage—they remain there, silent, offering the possibility of transit. A reminder that matter itself can lead to another realm of mental exploration.

La metodología del objeto-portal se fundamenta en dos ejes: el trabajo real del taller y las memorias culturales que atraviesan cada pieza. De un lado, los materiales concretos y las huellas visibles que dejan los gestos repetidos. Del otro, una genealogía que conecta amuletos, relicarios, arquitecturas y paisajes cinematográficos.

Los objetos, bajo este prisma, pueden transformarse en umbrales. Cada pieza de Las Ánimas es un objeto presente, tangible, pero al mismo tiempo un lugar donde lo cotidiano se abre a otra dimensión. Igual que los antiguos altares, estas obras invitan a atravesar un umbral. Permanecen ahí, silenciosas, ofreciendo la posibilidad de un tránsito. Un recordatorio de que la materia también puede llevar a otro lugar de exploración mental.